The Image as a Technology of Death

Reflections on the Image of the Netherlands, its role in colonial and political systems of preservation, political apathy, European self-absolution and the history of Dutch coloniality in Brazil.

If educational institutions are spaces of intellectual labor, it is crucial to define what this means. If labor refers to one’s willingness to exert effort, then thinking is not labor, if thinking is reduced to learning from curent paradigms and regurgitating them as they are. Hence, intellectual labor should be equated with ones willingness to question and, unless paradigms are continuously rescrutinized, across all fields, we will be intellectually held back. The following essay argues that acknowledging the Image as a technology of death and rethinking esthetic paradigms is essential to challenge colonial, capitalist and bigoted systems of preservation.

If the term “esthetic” alludes to the visual qualities of an image, then one ought to not only consider the image literally. It is under this framework that the idea of the Image, with a capital I, will be examined. Image with a capital because the imaging that will be discussed is the Euro-US-American canon dictating Images within the Western sphere of influence. As explained by Brazilian artist and embodied-researcher Puma Camillê; “esthetics are the first technologies of death”1. The Image can sustain claims in favor of a group, culture or environment’s glorification or abomination. Glorification upholds the position of its subject as Image maker, thus allowing the celebrated subject to oppress misrepresented (villified) groups. The existence of these systems of preservation should urge image makers to take control of Image production.

This essay will discuss the claim that the Image is a preservation system, with reference to the history of Dutch colonization in Brazil as a case study.

The Image and colonial memory:

The Image has the capacity to stagnate political systems, thus upholding existing technologies of oppression. In other words, the Image is a method of political preservation as explained by Bilal Khbeiz in the essay; Modernity’s Obsession with Systems of Preservation; “Despite modernity’s obsession with fragility and its aspiration to produce instruments of preservation, it is unable to preserve bodies—so it resorts to preserving images”2.

Indeed, multiple Western institutions uphold images meant to preserve the ocidental political landscape. The Netherlands, as a country, is a great example, given Dutch citizens unawareness and general disconnection to the attrocities committed by their kingdom in the colonial era. Most Dutch people wouldn’t associate the Dutch “Golden Age” to Brazil and would certainly not be aware of the horrors committed by Dutch settlers in the Americas thoughout the mid 1600s. Historian Alex van Stipriaan comments on the “historical narrow-mindedness” of the Dutch and explains that it is in large part because historians, until the 1980s, wrote about colonial history from a patronizing perspective, the colonized were rarely the center of historical narratives ( and nowhere else in Europe while we are at it). Although, in the Netherlands, the historiographic field has moved far beyond this, van Stipriaan elaborates that a derogatory and redutive Image of the colonized persists in the public consciousness, since the historians that still defend these views are more often given a platform by mainstream media3.

This phenomenon can also be observed in Brazil from a reversed point of view; many Northeastern Brazilians still endorse the Image of the “good” colonizer. The Dutch, for their religious and ethnic tolerance, along their contributions to the region’s rapid economic growth in the 17th century, are still regarded as “better” colonizers than the Portuguese. Mentions of Count Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, the representative of the Dutch crown in Brazil, remain prevalent in the media and politics of Recife, originally Mauritsstad and capital of Dutch Brazil. The politicians of the state capital of Pernambuco often reference Nassau in their speeches to further assert themselves as responsible rulers4.

It is worth noting that this myth is maintained in the contemporary Brazilian public consciousness in part due to the Netherland’s current politically “progressive” Image. From the late 1970s onwards, the Netherlands began a “branding” process that depicted it as a socially liberal yet economically developed nation. Examples such as the existence of coffeeshops (where marijuana consumption and purchase is tolerated), gay marriage and famous red light districts alongside a strong economy are used by mainstream neo-liberal media to justify the Netherland’s contemporary excellence. Naturally, this also resonates with the Dutch populace as it upholds eurocentric cultural hierarchies that (to their eyes) justify their “civilized”5 status in relation to less “developed” countries. Ultimately, this Image allows the Dutch to not feel implicated in their own country’s role in the maintenance of colonial and capitalist systems, both contemporary and past, they have moved past the barbarity of war and oppression. The Image goes uncontested.

Dutch people never learning about the destruction of South American ecosystems for sugar cane and Brazil wood monocultures, or about how these industries contributed to the displacement and enslavement of 350 000 West Africans in the 17th century alone are, simultaneously, examples of a cause and a consequence of the unconstested Image. Indeed, if the Image goes unchallenged, then the Dutch public consciousness still feels a connection to the colonizers of their past. This results in the portrait of people such as Marten Soolmans being some of the most praised possessions of the renowned Rijksmuseum, despite his wealth being the products of his ownership of sugar plantations, refineries and an enslaved workforce6.

It is crucial to acknowledge the political connection Dutch people have to their colonial past because this link is further proof that the Dutch “progressive” Image is a construct meant to stagnate the Dutch political landscape, thus allowing already existing systems of oppression to perdure, or in some cases, strengthen.

Self-absolution, scapegoating and the return of populism:

The “progressive” political Image conveyed is that of a country that has solved all their issues. No poverty, no discrimination, no inequality, etc… However, this is simply not the case. Privileged white Dutch citizens still benefit from the country’s colonial past. The best example being the Dutch wealth gap, which according to statistics from the World Inequality Database7, won’t stop growing since the late 90s and is one of the starkest in the world. The risk of being under the poverty line also increases if you are in a large Urban center such as Rotterdam or Amsterdam8, which house larger shares of immigrants and BIPOC people than rural municipalities. This correlation cannot be overlooked. Yet, Dutch people remain complacent to their own government’s fault in their country’s flaws.

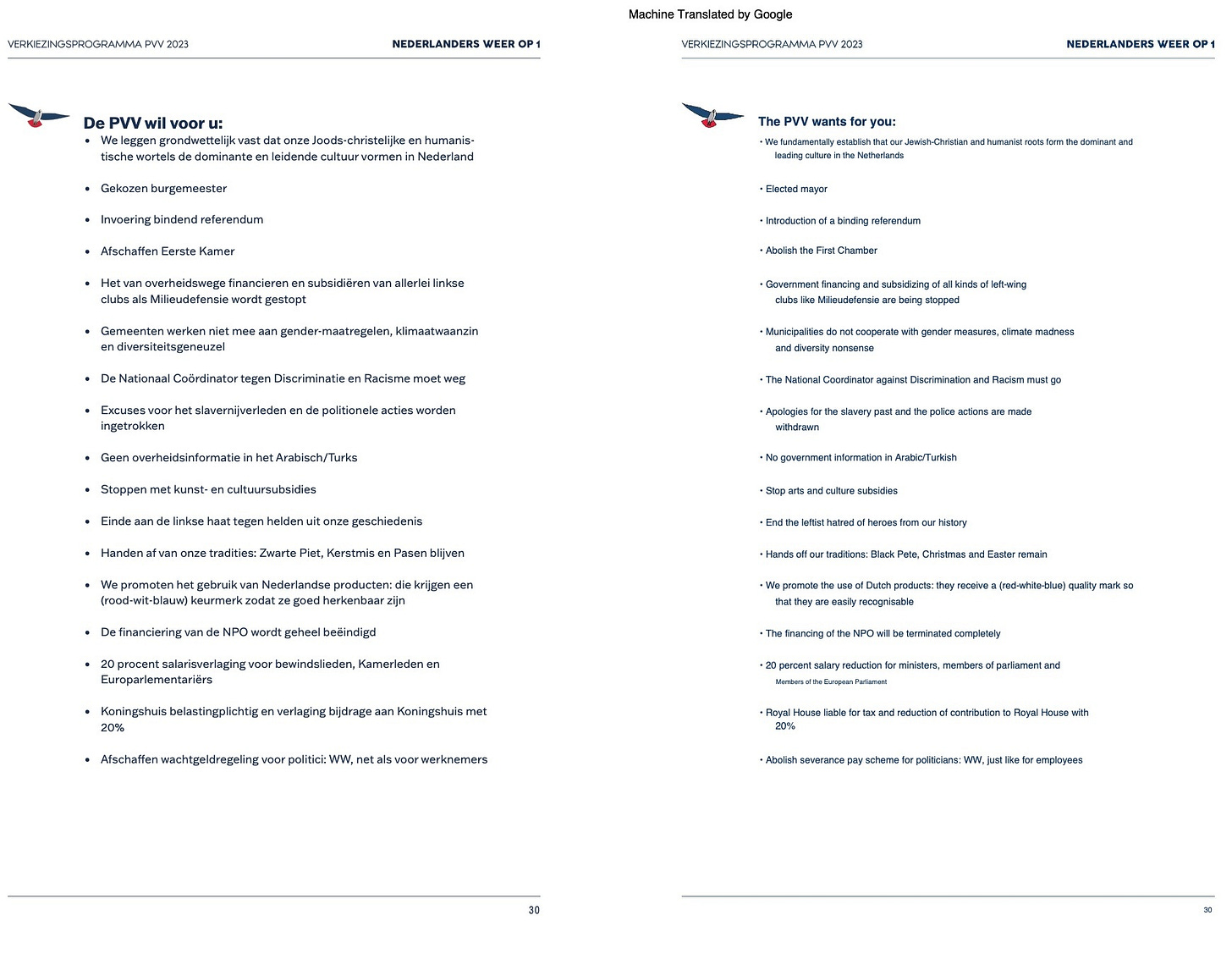

Unfortunately, because this Image of the Netherlands is upheld, issues such as the housing crisis (since 2021), inflation and rise in criminality are blamed on foreigners through populist discourse which has been gaining popularity for the past few years. This ultimately led to electoral victory of the extreme-right wing political party PVV in 2023, it became the party with the most seats in the 150-member house of representatives. It’s head Geert Wilders, is an outspoken islamophobe and xenophobe. This party knows intimately about the power of the Image, otherwise the PVV wouldn’t have included the following statements in their 2023 political program; “Apologies for the slavery past and police actions are withdrawn”; “Quitting art and culture subsidies”; “End of left-wing hatred of heroes from our history”; “The National Coordinator against Discrimination and Racism must go”; “No government information in Arabic/Turkish”; etc…9

Taking agency over the Image and subverting the canon:

Taking into consideration that the Image can withhold such devastating power, one wonders, how can this power be dismantled? How can cultural workers position themselves against this?

If research that opposes canon narratives can reshape the Image, then visual workers, and anyone working with the construction of the Image, should consider centering their esthetic labor around research and contextualization.

In her essay, Difference without Separability, Denise Ferreira da Silva analyses the mechanisms of modern thought and how the idea of absolute Reason is a mechanism of oppression. the capital R Reason discussed in her text supports the creation of the racial grammar that sustains the existence of The Other. A racialized, fetishized or marginalized Other that suffered the violences of modernism up until the neo-liberal society we live in today. Although in her text she is discussing this with relation to language, I believe her reasoning can be applied to the Image as well. She explains that “An ethico-political program that does not reproduce the violence of modern thought requires re-thinking sociality from without the modern text”10. It is equally important to rethink the Image beyond the modern canon, it is important for artists and those working with images to revisit the past to better understand the future they would like to portray.

An example worth comparing to this logic is the developments in Brazilian archeological studies from a queer perspective. Until the 21st century, Brazilian archeology was developed through the acquisition of irrefutable facts and scientific objectivity, thus completely excluding social perspectives that would refer to feminist or queer studies. Theories on the origins of sexual and gender divisions amongst indigenous societies were made based on a Western paradigm of male domination; Indigenous categories of gender were never considered. Fortunately, nowadays many archeologists are exploring the field with a regard for queer and feminist theory, thus distancing themselves from the Images conveyed by western-centered narratives. Multiple research projects on this topic are compiled in a bibliographic research article by Laura Pereira Furquim and Camila Pereira Jácome; Gender and Feminist Theory in Brazilian Archeology: From Gender Dismorphism to the Queer Spring [Teorias de Gênero e Feminista na Arqueologia Brasileira: Do Dimorfismo de Gênero à Primavera Queer]11.

All visual makers and workers should follow this example and find ways to operate beyond what the canon expects of them. As Ismatu Gwendolyn explains in her essay; There is no Revolution Without Madness; “There is no iteration of Western, sanitized Reason that will co-sign the destruction of itself”12.

Conclusion:

Ultimately, the Image can transform as much as it can stagnate. Those working with esthetics, in the literal and figurative sense, should consider their agency vis-à-vis the Image’s contruction and destruction. Artists should reflect on the histories and contexts their artistic practices fall within to better shape the future of the Image. But they shouldn’t be the only ones, art historians, curators, sociologists, economists, journalists, etc… should always be mindful of the power their words hold in the construction or dismantling of Images. It is important for academics to consider the ways in which their claims may contribute to the abomination of groups, cultures, or environments and how this vilification can sustain claims to violence, in all its meanings, against these subjects. It is important to acknowledge the Image as a technology of death.

Puma Camillê, “Masterclass by Puma Camillê: The Intersection of Vogue and Capoeira” (Framer Framed (Amsterdam-Oost), October 31, 2023).

Bilal Khbeiz, “Modernity’s Obsession with Systems of Preservation ,” E-Flux Journal, no. 8 (September 2009), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/08/61379/modernity-s-obsession-with-systems-of-preservation/.

Cath Pound, “How the Dutch Are Facing up to Their Colonial Past,” BBC News, February 24, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210601-how-the-dutch-are-facing-up-to-their-colonial-past.

Anderson Fernando Rodrigues Mendes, “O Mito Do ‘Bom Colonizador Holandês’: O Imaginário Sobre a Colonização Holandesa Em Pernambuco” (thesis, 2019).

The word civilized is used in reference to a conversation the author had with a Dutch colleague during which the colleague affirmed that they were “more civilized” in the Netherlands than in Islamic countries.

Cath Pound, “How the Dutch Are Facing up to Their Colonial Past,” BBC News, February 24, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210601-how-the-dutch-are-facing-up-to-their-colonial-past.

“Netherlands - Wid - World Inequality Database,” WID, accessed December 11, 2023, https://wid.world/country/netherlands/.

Cbs, “How Many Families Are at Risk of Poverty?,” CBS, January 17, 2022, https://longreads.cbs.nl/the-netherlands-in-numbers-2021/how-many-families-are-at-risk-of-poverty/.

Partij voor de Vrijheid, Verkiezingsprogramma 2023 (Partij voor de Vrijheid, 2023), https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.pvv.nl/images/2023/PVV-Verkiezingsprogramma-2023.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiKuOPUz7mKAxU5zgIHHZQPIEIQFnoECBQQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3p19yOmY4ncv7Y1KMXZZmG.

Denise Ferreira da Silva, “ON DIFFERENCE WITHOUT SEPARABILITY,” 32a Bienal de São Paulo (dissertation, 2018).

Laura Pereira Furquim and Camila Pereira Jácome, “Teorias de Gênero E Feminismos Na Arqueologia Brasileira,” Revista Arqueologia Pública 13, no. 1[22] (2019): 255–79, https://doi.org/10.20396/rap.v13i1.8654825.

Ismatu Gwendolyn, “There Is No Revolution without Madness.,” There Is No Revolution without Madness., November 9, 2023, https://ismatu.substack.com/p/there-is-no-revolution-without-madness.